The Wolves Passed Here

John Beaton

The Wolves Passed Here

John Beaton

© 2002 by John Beaton

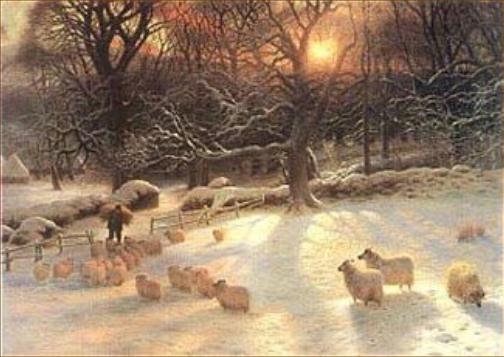

Cover Art:Shortening Winter’s Day by Joseph Farquharson

Published by The New Formalist Press

XHTML & CSS design by Leo Yankevich

River Woman

Did you ever fall in love with a riverand feel her sinews slide across the land?

Did her undercurrents ever make you quiver

and suck you down and down

through breathless dreams to drown

in turbulence of bubbles and glistening sand?

Is she the wild Stikine or Tatshenshini,

is she the summer-silked Similkameen,

is she the lithe long-legended Homathko,

are her eyes the glacier melting turquoise-green?

Did you ever let her flowing sweep you downstream

and lose your stone-held footing in the spate?

Did she flush you canyon-tossed upon a sunbeam,

sluice raceways through your mind,

careen you fast and blind,

then glide you leaf-like down her pools, sedate?

Were you ever cradled softly in her valley,

borne on a straining sheet of shining light,

turned slowly in a silent swan-like ballet

rocks sliding by below,

the land an upstream flow,

your thoughts a swirling haze of green and white?

Yes, she’s the wild Stikine and Tatshenshini,

yes she’s the summer-silked Similkameen,

yes she’s the lithe long-legended Homathko,

her eyes are the glacier melted, turquoise-green.

Wolves

I’m wakened, drawn towards the ice-thin window,to witness scenes as faint and still as death.

How bare the moon; how bare the trees and meadows;

sky’s pale maw overhangs

earth bleached beneath star fangs.

Night’s curled lip sneers on shadows

of mountains set like teeth.

Two bow-waves shear the median of the valley,

iced hayfield yields as feral muscles glide;

hoar-frost disturbed by wakes of live torpedoes,

grey shoulders breach and lope,

implode and telescope,

impelled by ruthless credos

of chilled and vicious pride.

The wolves tear savage furrows down the dreamland,

their eyes are shined with blood, their mission clear;

grass swings back shocked to green behind their passage,

twin tracks traverse the vales,

cold comets trailing tails

leave, scarred in frost, their message:

the wolves, the wolves passed here.

Woman In The Wind

Sheets of rusted corrugated ironclatter in the gusts against its walls—

the black house mossed with memories of childhood.

It passed like sunsets blushed across the kyles.

A teenaged bride, she wed her next-door neighbor;

one gateway and she crossed her line of blood.

Today that field-gate lies unhinged and fallen,

half-sunk in a half a lifetime’s puddled mud

and only washing-line connects the gate-posts.

Three shirts with arms extended tug and flap—

a man, two boys. She sees three crucifixions

and thinks of all the prayers and benedictions

they’ve counted on to save them from mishap.

Their row-boat rounds the Cregan to the Sound

of Raasay out of Camastianavaig Bay.

Black cormorants, like mourners, watch them pass

behind Ben Tianavaig then fade away.

At tide-change there’s a hush as waters still.

Red cod in congregations prey and gulp

the eels that undulate like blowing rags

as hand-lines search their sanctuaries of kelp.

Clouds glisten, haloed by a hidden sun.

The brightness weakens to the creak of oars.

Then wingless shadows fly across the heather,

gray waves of swelling rain bring foul weather

as storms begin to sweep the open moors.

This morning and each morning since she married

she’s borne the water-buckets from the burn

to wash away the woad of savage living

expecting neither respite nor return.

From unrelenting slime and sweat and smearings,

she keeps the gate and dares the coming squalls,

extracts the wind’s last spit-less drying breath;

but now both rain and iron rattle on walls.

In headscarf, tallowed boots, and threadbare coat

she wears for milking and when going for peat

she pulls the clothes-pegs, hoping that it brightens;

instead the cowl of gloom draws in and tightens,

and rainspots on the clothes seal her defeat.

Now serried whitecaps charge the assembled leagues

of shoreline cliffs then crash like cracks of doomsday

and rise as giant clamshells on the rocks;

though bow to blow, four oars can make no headway.

They slash their grounded lines and blisters tear

from callused hands; and limbs and torsos, wood—

one streaming sinewed beast impelled by fear—

resist the pounded Cregan’s beatitude.

No bell, just stony silence from the kirk

where ministers tell all they’re unforgiven

until they die, then say they’ve gone to heaven,

cold comfort as the combers go berserk.

She steps inside and fights to shut the door.

Outside the ravens huddle under haystacks,

and seagulls switchback into battering gales.

The iron sheeting flies. She finds some sacks

to caulk the draughty door, then lifts the wash

and squeezes hard to feel if it’s still moist

with water hauled before her men-folk rose;

then grasps these family icons to her breast,

damp armfuls of limp empty cloth, and knows,

as surely as the sun will set forever

beyond the kyles, as surely as the kirk

will keep its foregone verdicts under cover,

that, whether she must face a widow’s grief,

or they return expecting her relief,

until she dies, one of two hells awaits her.

Caledonian Pines

The pines stand tall upon the lochan isles;the ancient Woods of Caledon, they’re all

that’s left untouched by centuries of fire—

man’s pall, a shroud of smoke from bens to kyles.

Age-toughened, brittle, jagged, gray of limb,

half-fossilized these hardy few survive,

remaindered by their moats of mountain rain,

alive, small stands, their yield not worth the swim.

Held high before their former fiefdom’s hills,

last green crowns cock to high ground, heather-skinned;

old clans alone, their branches seed with moans

the wind that bears them barren freedom’s chills.

House of the Waterfall

The glacier slides over the lip of the corrie,spreading its hands on the flanks of the Ben,

white fingers gouging the vees from the valley,

freezing and filling the folds of each glen.

It reached to the pool where the Bruiach Burn plunges,

house of the waterfall built on its bank,

gables and stonework where cypresses nuzzle,

banisters, cornices, dusty and dank.

Here once a garden with fences of birch-poles,

shedding their silverskin bark in the sun;

here tilting roses hung lounging and draping

and bird-netted strawberry cuttings would run.

Here once a mother’s voice twined with the tree winds,

love-filled migrations of laughter and care;

here once a father conducted the rope-swing

higher and higher through octaves of air.

The glacier recedes from the place of the waterfall;

the Ice Age relinquishes water and land.

A deep-frozen figure appears from the ice-dark,

a boy yet to surface from time’s running sand.

The sun-heat is chasing the ice from the valleys,

moraines and striations and tails trailed from crags,

erratics and drumlins, the glacier’s handprints;

the ice-boy exposed now in ice-water drags.

Here once adventuresome deeds at the waterfall—

brothers at play by the summer-deep pool,

catching small trout from the turbulent spangling,

drinking cooled sunshine from hands cupped and full.

Here once the mystery trout of the cataract,

ghosting himself at the close of each day;

head-and-tail rises of untold proportions,

a bard making lore with each line of his lay.

The waterfall’s there in the valley that bears it,

the pool at the bottom trades pewter for chrome,

and under the surface the pallid face slides by,

the boy from the glacier unborn in his home.

The boy on the rope-swing flew higher and higher

and leapt from his seat on the surge of the breeze;

he froze there an instant, the apogee life-long,

then sailed with the winds to a land overseas.

He left for one summer, for one summer only,

but the Fates of the migrants were playing coin-toss.

Heads he’s not coming, and tails he is staying.

Returnings were thwarted, his hopes turned to dross.

Then one day the mystery trout of the cataract

appears carrion-still on the shore by the crows;

his head and his tail and the bone that connects them

are all that they spare of his giant repose.

And the hand of the boy edges out of the water,

his fingers slip slowly up splines of the tail,

behind the wrecked gill-plate and out of the gullet,

the boy’s index finger probes, feeble and frail.

He slides back down into the sepia silence,

the fish’s gills waft in the waters of youth;

the Fates of the migrants play on with their coin-toss,

no heads and tails now turn their wagers to truth.

A jet-plane re-crosses the Atlantic Ocean,

an old heron sailing on world-weary wings;

an old man returns to the house of the waterfall,

and faintly he hears as the mother-voice sings.

His hair and his skin are all covered in ice-dust,

his eyes and his teeth are all yellow and lost;

he goes to the pool, to the pool of the waterfall;

it’s mid-summer frozen and powdered with frost.

And there in the black of the ice that confronts him,

the shape of a body affronts his soul’s core;

the tender white face of the boy from the garden,

preserved for the future with future no more.

The Combustion Of Apples

Old Gravenstein, your boughs are scabbed and mossybut you expand them graciously, a host

inviting passers-by to share the glossy

hospitality your bushels boast.

Your blossom spangled spring rain’s spectrumed prism

and dropped; green stippled you and turned to reds

and golds. They coalesce—spring’s pointillism

is smeared as autumn’s flaring wildfire spreads.

Now fanning winds gust leaves—sparks float to earth

and apples fall like coals. They’ll leave a tortured

candelabrum etched above a hearth

where ash still smokes—the frosted misty orchard.

Dusk. Across the mural of the sky

your portraitist depicts another scene:

he specks and flecks your boughs with nebulae

in blooms of carmine, salmon, gilt, and green.

And they too blend as space-dust avalanches

down columns light-years tall and then combines

in worlds that fall, like apples from your branches,

decaying as their core-stored sun declines.

Thus apple-trees and galaxies expire—

in dappled glades of universal fire.

Brothers of the Byre

The byre cleaves to the half-floor my father and uncle barrow-mixedand trowelled. Drawn, I pressed my hands to its wetness. Then rock by rock,

they raised the walls from broken crag, built rafters where iron was fixed

and there they kept the scythe, bridle, and trammel under lock

that went unfastened. I stared at knotted beams in days when rain

bee-lined down corrugations and dropped outside like ropes through fingers,

through tar-smells, through dung-steam rising to mist the lowering sky’s dank pane;

then winter came. Wind sledged below the roof—my memory lingers

on the wedge and the rend of the gusts; up-arched, the sheeting lever-ripped

and flapped. Persuading nails, the brothers crawled like earwigs under

a King’s Gold sky, then tarried inside for a dram. As last rains dripped

beside their slab, they toasted the storm. Villagers followed the thunder;

the years that rolled like Easter-stones left caves, not resurrections

and nets hung dry; rust stalked the waves of the eaves. One year or other

they buried her stillborn baby where the byre now stands—old recollections

of crosswise sticks, of wildflower bunches were marks of my older brother,

my mother tells me now. We stare at it, hand in hand;

I sense the beseeching fingers reaching higher, ever higher,

to clasp the handprints that dimple the floor, to be raised to the stormy land

our father and uncle worked together—brothers of the byre.

Woodsmoke

The stove is filled and fatted, large with logs,the damper’s turned down, flames have taken hold,

and woodsmoke mingles with the cedar fronds

of branchy giants outside in the cold.

It slithers through black boughs that screen the sky

then re-emerges white against the night

and curls towards the pale October moon

as though inhaled into its haloed light,

then cools and falls through hemlocks to the marsh,

spread like a slab of slate beneath the coils

of hoared and icy mist that snakes from reeds

and disembodies all that it embroils.

It’s here the woodsmoke settles down to hide

among that hidden frosty sea of mire

but leaves its pathway hung up in the sky,

gray rainbow flowing slow to ice from fire.

Entrained in draughts that draw towards the stove

a sigh, a breath combust and then entwine

and with the smoke ascend that starlit arch

then fall where pots of gold are said to shine.

The morning’s kindling rouses slumbrous embers

and night’s enchantments spirit back to bed;

slow lilting flames cast figures in the fire-glass;

gold glitters in the smoke plumes overhead.

We walk in sunlight shafts through autumn maples,

two leaves descend like flakes of gilded snow;

our interleaving fingers share the hearth warmth

of russet woods and woodsmoke’s afterglow.

Bed-time Story

The sun has smouldered low. Its flaxen lightdrizzles through the birches to the snow

where sheep stand still as haybales, beige on white.

A shepherd with a shoulderful of straw,

brindled by the shadows, softly walks.

The sheep flock round; he swings his load to strew

the strands on pillowed drifts like yellow locks,

then hastens homeward bearing sustenance

against the ghostly dark. He holds small hands

and spins his children tales of happenstance

and golden fleeces in enchanted lands.

Their minds woolgather. Snuggled down in bed,

they drift on snowy pillows; yellow strands

of hair glow like the hay their father spread.

Women Of The Ages

I’m the lass of Invergarry,singing by the loch alone

of the lad I was to marry,

of the baby in my belly

he begot but would not own.

I’m the mother of Glenfinnan,

feeding sons who gird and go,

dreading battles, ripping linen,

dressing wounds and watching crimson

drench the strips of my trousseau.

I’m the widow of Culloden,

sowed and reaped and left to weeds

till I'm winter-tilled and sodden,

till my tilth and clods are broken

by the cold that kills my seeds.

We’re the women of the ages,

wooed to walk the aisles of grief;

we’re the wear on well-worn pages

where posterity retraces

deeds of men in bold relief.

About the author

John Beaton was raised in the highlands of Scotland. He obtained an M.A. Hons. in mathematics and philosophy at Glasgow University, qualified as an actuary, emigrated to Canada, and became co-owner of a successful actuarial consulting firm. The firm was sold to a larger corporation and John continues to work for it as a Senior Vice-President. He divides his time among downtown Vancouver, an acreage on Vancouver Island where he and his wife have raised five children, and a cabin on Denman Island. He has been reciting his own brand of Scottish light verse at Burns suppers, ceilidhs, and Celtic festivals for many years, but came to grips more seriously with the craft of writing poetry in 2000. Since then his work has appeared in numerous print and on-line publications.