Visitation

Neill Megaw

Visitation

Neill Megaw

Acknowledgements:

Blue Unicorn, Candelabrum Poetry Magazine,

Ceilidh, East West,

The Formalist, Hellas,

The Lyric, Pegasus,

Poultry, South Coast Poetry Journal,

Tucumcari Literary Review

© 2002 by McNeill Press

Cover Art: A Woman Asleep by Johannes Vermeer c. 1656

Published by The New Formalist Press

XHTML & CSS design by Leo Yankevich

Blue Unicorn, Candelabrum Poetry Magazine,

Ceilidh, East West,

The Formalist, Hellas,

The Lyric, Pegasus,

Poultry, South Coast Poetry Journal,

Tucumcari Literary Review

© 2002 by McNeill Press

Cover Art: A Woman Asleep by Johannes Vermeer c. 1656

Published by The New Formalist Press

XHTML & CSS design by Leo Yankevich

Stone in the Shallows

Plain as can be, in the rivulet’s middle, the stoneSits contentedly. Oh, he will roll

If the water really insists, but, left alone,

A civil stability is his goal.

Consider: by just persisting there that way

In a current that flows nine miles an hour,

He swims upstream two hundred miles a day

Without the slightest display of power.

To pride, ambition, and self-indulgence dead,

He does not ask for a sunnier sun,

Water more liquid, a softer river bed;

No smaller neighbor he’d outrun.

Are these his most heroic qualities? No:

Observe his total concentration.

Ripples and floating petals, the fish below

Cannot unclench that meditation.

Profoundly he broods, judicious cannonball,

On life and death, on science and art;

He sees, he feels, the tragedy of it all,

But soldiers on, old lionheart.

Afternoon on a Terrace in Mississippi

In the pomegranate, a hummingbird hard at work,Switching about, quizzing the pink–gold blossoms,

A three–inch cobalt and emerald jackhammer

Drilling for hidden treasure, unperturbed

By the party close below, the children’s clamor,

The dancing couples, the servants with trays of glasses.

Lost in his labor, fretting and fussing, burning

Calories almost as fast as he sips them, intense

As a coal, he decorates but does not share

Our leisure, his pulse-rate breaks all records, he blurs

Our sight with the effort of hanging fixed in air,

Forging a jewelled calm from turbulence.

This pomegranate and hummer do not belong

Over here, they belong in an ancient Persian garden

Or a garden in ancient Persian tapestry,

With butterflies, bulbul and roses, and a marble font

Where a milk-white stallion drinks, a dream of peace,

A world where there is such a thing as pardon,

Painfully though that world was created, stitch

By bitter stitch, year after year, by the hands

Of the humble, those who would never have time to admire

The vision they shaped for the happier-starred, the rich.

I see the dance of those beautiful hands in the fire.

I see how slow the passing caravans.

The Linen Chest vs. the Laundry Hamper

Fold after fold of the coolest, freshest linen,Exactly the length and breadth of the chest, filled up

As snugly as milk in a jug to the very lip,

Socialized and sanitized,

Tenderized, tranquilized,

Drifting as one in a dream of sanity, grace

A smoother and steadier pace,

A life less base,

A purer place:

Clearness.

Crammed in a fetid hamper any-which-way,

A motley tangle of sullied handkerchiefs, shirts

And blouses, bras and pantyhose, socks and shorts

Intertwining, mine-and-thineing,

Harlequin and Columbine-ing,

Stilled, at pause in the clumsy, bitter fight

To wring from each other and night

An ampler light,

A coupled sight: Nearness.

Double Dactyl for Emily

Fitfully-flitfullyEmily Dickinson

Peeked all around with her

Sight stroboscopical.

Shy little loner so

Eccentricissimal,

Outwardly Amherst but

Inwardly tropical.

Song for Anna

Anna, Anna, romancing-eyes Anna,As soon as you danced into view,

Anna, Anna, entrancing-eyes Anna,

I went bananas for you.

Oh, I fell just like a harpooned ox,

And from you I’ll never be free;

With you I could live in the boondocks,

Altoona would seem like Paree.

For Anna, Anna, magic-eyes Anna,

You can turn water to wine.

So Anna, Anna, tragic-eyes Anna

Say that you’ll always be mine,

And I’ll play the puppet clown, jumping

Or sprawling as you pull the strings,

Without you my heart would stop pumping

Though I led a life like a king’s.

Anna, Anna, my dreamy-eyes Anna,

Granddaughters should all be like you,

And Anna, Anna, moon-beamy eyes Anna,

I pray all your dreams will come true.

A Little Spin with Aunt Martha, Fifty-odd Years Ago

The most high-spirited woman I ever knew,chattering constantly, laughing, bursting out

in song (a terrible voice, she didn’t care,

she loved to sing, so much that she made others

like it too). She managed a brief quiet

for prayers, funerals and such, but mostly

chirped along in unrelenting cheer.

What I liked best about my aunt was the way

she drove her splendidly scraped and battered car.

My brother and I sat in the back with mother,

while father sat in front beside Aunt Martha,

trying vainly to hide his panic while she

shrieked with laughter, pounding the steering wheel,

and turning around to share her glee with mother—

or waved and smiled to neighbors or pointed out sights,

eyes for everything but the road ahead,

skinning past parked cars in less than an inch,

veering sharply out to the left again,

oncoming drivers flinching away pale-faced,

their life expectancies pared by a month or two.

Oh, what fun, daddy and mommy’s faces,

to stop in the last splitsecond a hairsbreadth short

of the monster truck ahead, and then lurch off

on the green again convulsively, with merry

disregard for the clashing gears, the enormous

cloud of smoke she left behind—these days

her name would be environmental disaster.

She simultaneously braked and accelerated

her blissful way downhill, laughing, talking,

laughing till she cried, took off her glasses,

and blindly dabbed at her eyes with a crumpled hankie,

father’s hand now hovering near the wheel,

more moth than hawk, not yet quite steeled to pounce.

Oh, she could turn a grownup white as a sheet,

but one small nephew thought she was really neat.

Sleeping Woman

Slumped at last contentedly in sleepOver a book in her favorite chair, glasses

Fallen low on her nose, a small smile

Curling her lips, breathing slow and deep,

She has escaped the tyranny of dishes,

Soiled clothes, the implacable rain of dust,

The letters still to be answered, forms filled out,

The prison cell of the dully repetitious,

She is slim, quick, young, eleven again, a girl

In a garden that needs no care, or in a canoe,

Or hitching a handbar ride on daddy’s bike,

Or teaching a pretty new skirt a fetching twirl.

Soon enough she’ll wake a sixty-year-old.

Tread softly, friends, here everything’s delicate gold.

Visitation

Four a.m. Slowly he wakes,the poet, on his back in bed.

High on the ceiling above his head,

a bright flutter of whiteness. Flake

of paint? A moth? From his cocoon

he rises, sees: reflected light

through parted curtains from something bright

on the terrace below. He peers: the moon,

pooled in the shiny curl of a leaf,

fallen to tremble slightly there

upon the bricks in the chill night air.

Simple facts that stagger belief:

from the sun (now dark) to the moon, to the cup

of the leaf, then up through curtain chink

to dance on his ceiling, tease and blink

until from dreams he’s summoned up?

What clod could fail to respond to a sign

as bold as this? Right down the stairs

he tears, pajama-topped and bare–

footed, pours a glass of wine,

runs out on the terrace, glass held high—

“Whether a warning or benison,

kindliest promise, deepest curse,

bless you, leaf and moon and sun,

bless you, all you stars in the sky,

bless this whole damn tangled, intricate universe!”

Picnic in Vermont, with Ghosts

Twice canopied, high blue-and-whiteOver the green-and-white of blossoms,

Under scented apple trees

We sprawl, the wide snowflakes drifting

Down on our heads, the salad, the wine,

On the blanket spread on the grass below us,

The small curve of the baby asleep.

How many times like this pay back

The price of a life? One, two, three, four,

Seven, nine, eleven, a score?

The great Khalif Abd-al-Rahman,

With fifty years of peaceful rule,

Respected by even his enemies,

Took careful thought and counted up

His days of happiness. Fourteen.

Others have paid, in cash, in grief,

In blood, to set this feast before us:

Parents, strangers, the hosted poor,

All those gone but present now.

We can’t assume the burden of guilt

For all that pain. No more did they.

The best is just to ask forgiveness

For drawing them here as visitors,

And pour this glass of wine on the ground.

The Hand-winged One

He hangs by one leg upside down in a cave,Listening, always listening, even in sleep,

Unable not to listen, listening’s slave,

His sonar pin-pointing the faintest beep—

Or rather, the whole delicate globe of sound

Incessantly dancing, winking, semaphoring,

A chaos of messages speeding from all around,

Not one of which he can afford to ignore.

The formula for falling, sixteen feet

Per second per second, is stamped into his brain,

His instant statistics never lie or cheat;

And when he takes to the night, his true domain,

He knows, not knowing how he came to know it—

This ugly, timid, half-blind thing, the poet.

Birdbaby

My wife, the widely celebrated magician,Said ALLA-KA-ZAM, went skinny,

And produced from under her bowler hat

A small daughter with wings.

Her mother, remarkably kind,

Says this phenomenon is also mine,

Though my connection is really so remote

I feel like someone who forgot to vote.

She flies around our cottage gently bumping

The ceiling and walls and things,

Peeing down from time to time

A teaspoonful of rose water.

When hungry, she descends

To her mother’s beautiful breast;

When tired, she condescends to rest for a little

Curled in the nest of herself.

She is much too good to topple lamps

Or knock the hanging pictures askew:

These she contemplates gravely,

A hovering hummingbird

With serious views on art.

Too young to sing, she has an extensive repertoire

Of experimental burbles and bloops,

Like a fat mermaid learning the flute under water.

She is the very antithesis of trouble.

At night, when I’m changing her diaper,

It is a privilege to wipe her.

Her specialty is a creme caramel

With the rank and bracing smell

Of life, and strength,

And everything, everything working well.

On such occasions she makes clown faces at me,

Or offers philosophic observations,

Speaking in a slow pink sign language,

Or simply, serenely stares right through me,

Her eyes two blue alarm clocks in no hurry at all.

Sometimes we feel, oh, keep her inside, close everything up,

Shut all the windows, bar the doors,

Disguise her with pencilled wrinkles and witch’s beard,

Dress her in Cinderella rags and a white fright wig,

Hide her inside a nice big box.

No use, no use,

Another magician, on the bill already, will come,

Handsome, electric, and make her disappear,

Conjure her into a mist to slide out under the door

Or, finer grained,

Pass through the microscopic pores of the window pane,

And even extort our grudging consent.

But all that is a long while off,

Months and months away,

And now for many a sunny day

She’s ours, our jelly roll, our Stroganoff,

Our cup of tea that runneth over,

Our four-leaf clover,

Our fleur-de-lis.

Dipping and soaring devil–may–care

Around us, filling every inch of air

With delicate calligraphy.

What ease, what storm it is to love her,

No angel hierarchy above her.

For a Neighbor’s Child

Underneath this stone there liesThe little miss with the mockery eyes

And a giggle like a silver flute.

Her trust in life was absolute.

God was grey and needed mirth.

Lightly, lightly, gentle earth.

Three-triolet Biography

Spring SongThe triolet’s two-inch waterfall

Of rhyme will serve to fill a heart—

So clear its syllables, sure its call,

The triolet’s two-inch waterfall.

Mightier streams may churn and brawl,

Thunder down, dash all apart;

The triolet’s two-inch waterfall

Of rhyme will serve to fill a heart.

Daughter

When she was only six years old

Her quiet gaze could stop your heart;

One look, and you were bought and sold,

When she was only six years old.

She’s gone. One day a young man strolled

This way. No malice on his part:

When she was only six years old

Her quiet gaze could stop your heart.

Tryst

Hushed, the wind, now, here in the grass,

And my lovely girl lies close beside.

Whatever the future brings to pass,

Hushed, the wind, now, here in the grass.

How little it matters for me and the lass

That the life we dreamed of, fate denied;

Hushed, the wind, now, here in the grass.

And my lovely lass lies by my side.

A Place Where Three Roads Meet

CHANGING: A Tale for the Older ChildHe rose at dawn, the old, old man, drawn

To his bedroom window, and saw below the stranger, a mare,

A slender palomino mare, fair

As a lily, waiting, serene, the quiet plumes

Of her breath feathering into the mist. Time,

He knew. She had been sent to carry him to death.

Nightgowned, capped, down the stairs he went,

And over the grass, the cold dew waking his feet.

And mounted, clumsy, stiff–no lithe young rider,

And neither saddle nor bridle—but she was patient,

Waiting for fingers tangled deep in her mane,

And pacing slow till he was more at his ease astride her.

Midmorning, they came across a shadowed stream.

The mare lowered her muzzle to drink, then pawed

In creekbed stones: a silver circlet gleamed,

With a ruby to dangle over a prince’s brow.

No proper crown, he grumbled, getting down,

The stone, much too large to be real. But it was real.

The beautiful mare then led him to a cave;

Inside, a chest fragrant with fresh linens,

Lustrous silks, and a suit, a suit to stun

Silent the whole floor at an emperor’s ball,

And gloves of silver to match his circlet-band.

The old man glittered as they rode on again in the sun.

Lacing, unlacing, and loosening slowly down

In a stately, glittering–scaled procession of esses,

The monarch snake descended and advanced;

The aged man dressed like a prince stood waiting,

Motionless, staring as if entranced.

The heavy coils slipped round him, one by one.

They closed him into a well of cool dry muscle

That now began to tighten, gently, at first,

Its intricate grip on him more nicely arranged,

Then harder, harder, harder, until at last—

As all along the canny old man and guessed—

He popped right out of his skin like a pip from a pinched grape.

He didn’t care that the snake was bolting down

A horrible banquet of brittle old-man’s bones,

Sadly shrunken sinews, spotted skin—

Too bad about those clothes and the prince’s crown.

He thought, and sighed, but fair is only fair,

The labourer, as they say, is worthy of his hire.

Now new–born wet, a snake himself, it seemed,

All straightness melted away in pure curves,

He reveled in snake-locomotion, the play

Of virtuoso belly-plates that swam him

Swervingly over the ground and through the trees,

Caressed by grass and fern parting as if in a dream.

What course he steered, and what he hoped to find,

He didn’t know, and yet there was a course,

And he was steering it well, he knew, as well

As cousin eel, threading currents, blind,

Across the wide Atlantic, coming home

Again, latchkey stretched out straight, ready for lock.

Once out of the woods, the path was suddenly steep;

He was climbing boulder-littered badlands,

Mesas slashed with long-dry river canyons,

Higher, snow-clogged valleys edged with crags;

At last, the harsh crags themselves, and whistling,

Bitter winds that slashed like scythes of sharpened ice.

That afternoon was a long, long afternoon.

No smooth gliding now, but strain and strain—

Yet straining gave him voice enough to grunt with,

Rocks taught lessons in rigidity,

Fissures, corners, narrow ledges soon

Told him: find some means of prying, wedging, clawing.

This climbing seems to change the climber, he thought,

But had no leisure to consider more

Until he reached a lake cupped among peaks

Not far from the top of the world, yet so well sheltered,

Only a thin white ruffle hemmed its skirt.

I know this lake, he thought, I know this rocky shore.

And, stopping to wonder how it was he knew,

He tossed three stones in the water before he saw

He had arms again, and legs—a man, strong-thewed,

Hands like iron, bearded, in rude leathers.

No longer tired, he climbed up to a ledge

That over-looked the lake. There was the castle. His.

A hail: the drawbridge lowered, he strode across,

Passed through the high, empty, echoing hall,

Up stairs, along the mirrored antechamber

Into the throne-room, where his father and mother,

Crowned, sat smiling, dead long since, of course,

But pleased to see their child, the prince, at home once more.

I have returned only to say goodbye,

He said. So much to do, and the day near gone.

He kissed his mother twice and touched her face,

Embraced his father strongly, a long embrace,

Knelt for blessing and farewell, stood,

And turned from them at last, retracing his steps

Past the mirrors, down the marble stairs,

Through the echoing hall, with its arms and pennons,

Louder, back across the wooden bridge

To where a great black stallion stood alone,

Saddled, eyes a-flash in the roseate light,

Stamping a metalled hoof down hard, hard, on stone.

SEARCHING: The Forever Cave

I have known caves. Small ones, good enough

For getting out of the rain, with a black circle

Where someone cold and wet once huddled, steaming.

Deeper ones, where you stop dead in your tracks

As the panicking nostrils suddenly register Bear,

Longer, rougher, trickily-crookedy ones

Waiting for a match’s flare to leap,

Baring its fangs, then grinning—See? Just rock-

Gothic-cathedral caves where stalagmites

Lift up their blindman’s blunted fingertips

Straining to join the daggertips above.

And vast, shattered-Colosseum bowls

Destroyed for some outrageous, god-defying

Performance thousands of years ago, or millions.

The cave that haunts me, though-another world—

And, no, I do not mean the cave of death,

For those who enter that cave simply vanish—

But like the cave of death in going on

Forever, chambers opening into chambers,

Passageways and corridors circling back

From all directions, interconnecting, splitting,

Rising gently or sharply, falling off

Again in sweet descent or black abyss.

This is no labyrinthine prison, trapping

Forever those who stray too deep in its maze;

Openings everywhere beckon above

To the air, to sanity, to other people.

At evening, after a long day’s exploring,

One can always climb out, or pitch one’s bedding

On the floor under a high, rocky window

And, looking up like someone drowned in a well,

Watch a handful or two of stars, no more,

Move over, guarding you as you fall asleep.

Not hatred or envy of others, nor arrogance,

Nor fear—or so I like to think—drives me

To search this endless cave. Greed, no doubt,

For secrets or for treasures hidden there,

And certainly so vast a space must hold them,

But mostly need and love; for she is there,

I know, the unimaginable she,

And I can only find her there. We’ll meet,

And she’ll be perfect—and I, not perfect, of course,

But a little the better for having sought her out,

And we will kiss, caress, and mate, and if

“Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin” appears

In letters on the wall, we’ll laugh and read it,

“Tried in the balance, and, thank God, found wanting.”

And then, either we’ll climb, hand in hand

Like Adam and Eve, up to the real world

And the sun and real people, or else we’ll linger

A while, down there, listening to the peace.

A lie, a dream. Or true, but not entirely:

Perhaps I’ll find her an hour, a moment, too late;

We’ll meet, exchange a word or two, and part.

Perhaps we’ll never meet. Perhaps I’m wrong

And she doesn’t exist, never has existed.

The searching for her may be what I need,

And searching for her there, no other place,

There in the lonely, intricate, echoing dark.

I have known caves. Small ones, good enough

For getting out of the rain, with a black circle

Where someone cold and wet once huddled, steaming.

Deeper ones, where you stop dead in your tracks

As the panicking nostrils suddenly register Bear,

Longer, rougher, trickily-crookedy ones

Waiting for a match’s flare to leap,

Baring its fangs, then grinning—See? Just rock-

Gothic-cathedral caves where stalagmites

Lift up their blindman’s blunted fingertips

Straining to join the daggertips above.

And vast, shattered-Colosseum bowls

Destroyed for some outrageous, god-defying

Performance thousands of years ago, or millions.

The cave that haunts me, though-another world—

And, no, I do not mean the cave of death,

For those who enter that cave simply vanish—

But like the cave of death in going on

Forever, chambers opening into chambers,

Passageways and corridors circling back

From all directions, interconnecting, splitting,

Rising gently or sharply, falling off

Again in sweet descent or black abyss.

This is no labyrinthine prison, trapping

Forever those who stray too deep in its maze;

Openings everywhere beckon above

To the air, to sanity, to other people.

At evening, after a long day’s exploring,

One can always climb out, or pitch one’s bedding

On the floor under a high, rocky window

And, looking up like someone drowned in a well,

Watch a handful or two of stars, no more,

Move over, guarding you as you fall asleep.

Not hatred or envy of others, nor arrogance,

Nor fear—or so I like to think—drives me

To search this endless cave. Greed, no doubt,

For secrets or for treasures hidden there,

And certainly so vast a space must hold them,

But mostly need and love; for she is there,

I know, the unimaginable she,

And I can only find her there. We’ll meet,

And she’ll be perfect—and I, not perfect, of course,

But a little the better for having sought her out,

And we will kiss, caress, and mate, and if

“Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin” appears

In letters on the wall, we’ll laugh and read it,

“Tried in the balance, and, thank God, found wanting.”

And then, either we’ll climb, hand in hand

Like Adam and Eve, up to the real world

And the sun and real people, or else we’ll linger

A while, down there, listening to the peace.

A lie, a dream. Or true, but not entirely:

Perhaps I’ll find her an hour, a moment, too late;

We’ll meet, exchange a word or two, and part.

Perhaps we’ll never meet. Perhaps I’m wrong

And she doesn’t exist, never has existed.

The searching for her may be what I need,

And searching for her there, no other place,

There in the lonely, intricate, echoing dark.

MAKING: The Blue Jug

Glass, a light sapphire, fairly thick.

Below, a quart-size bowl, six inches high,

Diameter, five inches, the bottom flattened

And dimpled up inside like a wine bottle;

A stubby neck above, an inch and a half;

A handle, parsnip–shaped, its thin end rising

From higher than midpoint on the bowl, then curving,

A gracefully fudged right angle, to join the neck

With its thicker end flush at the very top.

No pouring spout, a stopper once, now lost.

Mid-twentieth century, but off-hand blown

In the older, plainer style, in West Virginia.

Some blems and bubbles, a punty mark on the dimple.

But filled with plain tap-water it becomes

The very Idea of blue, of water, of glass,

Of jug, all four together, bluewaterglassjug.

And even empty, it would be ideal

Alone as a first exercise in painting;

Ideal, placed with other simple things,

For still-life lessons, a little further along.

And finally, you could fill it with white flowers:

The scraggle of stems below in the water would look

As if held hostage there forever, caught

In deep-sea crystal, the delicate blossoms above

Like spirit trying to free itself from matter.

Glass is miraculous, a solid liquid

That gets more viscous but never all-the-way hard,

Not crystallizing, cooled to its freezing point.

That’s why we’re seeing through it, darkly, now,

This small creation risen out of the fire,

Its elements common: sand, quicklime, ashes,

“Cullet,” parings and broken glass from the past—

And sweat, determination, hard–won skill.

The blower of this jug, inspecting, saw

That it was good in spite of imperfections;

He knew, as well, that time would make it perfect

If properly cherished-set on a windowsill,

Perhaps, to hold the sun. He set it down

And then went on to make a better jug.

Glass, a light sapphire, fairly thick.

Below, a quart-size bowl, six inches high,

Diameter, five inches, the bottom flattened

And dimpled up inside like a wine bottle;

A stubby neck above, an inch and a half;

A handle, parsnip–shaped, its thin end rising

From higher than midpoint on the bowl, then curving,

A gracefully fudged right angle, to join the neck

With its thicker end flush at the very top.

No pouring spout, a stopper once, now lost.

Mid-twentieth century, but off-hand blown

In the older, plainer style, in West Virginia.

Some blems and bubbles, a punty mark on the dimple.

But filled with plain tap-water it becomes

The very Idea of blue, of water, of glass,

Of jug, all four together, bluewaterglassjug.

And even empty, it would be ideal

Alone as a first exercise in painting;

Ideal, placed with other simple things,

For still-life lessons, a little further along.

And finally, you could fill it with white flowers:

The scraggle of stems below in the water would look

As if held hostage there forever, caught

In deep-sea crystal, the delicate blossoms above

Like spirit trying to free itself from matter.

Glass is miraculous, a solid liquid

That gets more viscous but never all-the-way hard,

Not crystallizing, cooled to its freezing point.

That’s why we’re seeing through it, darkly, now,

This small creation risen out of the fire,

Its elements common: sand, quicklime, ashes,

“Cullet,” parings and broken glass from the past—

And sweat, determination, hard–won skill.

The blower of this jug, inspecting, saw

That it was good in spite of imperfections;

He knew, as well, that time would make it perfect

If properly cherished-set on a windowsill,

Perhaps, to hold the sun. He set it down

And then went on to make a better jug.

Pennywhistle Song: the Suitor’s Farewell

Flowers and herbs, each spring and summer day,I used to bring to you, bring to you,

Daisies, violets, mint, rosemary, bay,

So that their mingled scents would cling, yes, closely cling to you.

It’s fall. No flowers. Just from the brook, a stone

Is what I bring to you, bring to you,

A pretty pebble, cold to the very bone.

Keep it, my love. Goodbye. And may it sing to you, sing to you.

Summary

We danced and played the livelong dayAnd then, in the usual way, came night;

But even the frowners would have to say

We danced and played the livelong day.

Knowing, of course, we would have to pay,

Our laughter warm, our eyes alight

We danced and played the livelong day,

And then, in the usual way, came night.

Pantoum: Ebb Tide

The tide, as slow as usual, edges out,The beach broadens, silvery, down to the sea—

But there’s a hint of hesitance, even doubt,

An all but extravagant generosity.

The beach broadens more silvery now, the sea

Responding to subtle cues from the moon up there,

An all but regal generosity,

Perhaps a gentle comment on our affair.

Responding still to cues from the moon up there,

Your eyes turn warm whenever you look my way,

And yet, a delicate measure of our affair,

Your glance more easily now is drawn away.

Your eyes are warm when you happen to look my way,

But also hesitant, shadowed now with doubt,

Your glance more readily turns itself away,

The tide, slowly as usual, edging out.

She Enters: Tableau

Everything is stopped when you appear;The wine, the flowers, candles instantly know.

The disarray’s now perfectly disposed:

Textures, the light—you’ve made us a Vermeer.

It must be so: I’m standing frozen here,

Like chairs and tables, one of your helpless beaux,

Caught in a suddenly altered atmosphere,

Unable to approach, unable to go.

Everything is stopped when you appear;

Prettiness has powers, it charms, endears,

But sheer beauty falls like a massive blow.

The slightest glance obliterates all we know,

All that only a moment ago was clear.

Everything is stopped when you appear.

The wine, the flowers, candles instantly know.

Oread

We found the place, my cousin Sheila and I,Idiots gone for a climb on a sweltering day—

Invisible from below, hidden by trees,

A modest waterfall, halfway up

The steep hill behind our cabins, had carved

A wide but shallow basin in the rock,

From which it overflowed to slide in a sheet

Across a smooth, slightly tilted slab,

Green with moss, then fall again in driblets

All around the semicircular edge

To splatter and vanish into the pines below.

I was nine, and desperately shy,

But Sheila was eleven and bold as brass.

Her clothes were off and she in the pool, howling

At the cold and splashing me, before

My shoes and socks were off. While she jeered,

I stripped to the buff, self-consciously, and joined her.

Later she climbed from the basin onto the slab

To look at the view. “The moss is soft,” she said,

“It tickles your feet.” She stood straight as a reed,

As if grown out of the water at her ankles.

“Come and look,” she said, but I couldn’t move.

Darwin’s Portrait of Death

Legs crossed, he sits outside atop his table,The perfect medieval tailor, stitching, stitching,

Making minute adjustments here and there—

More jaggedness for the lobster’s larger claw,

More delicate frills for the sea anemone,

Buttons ever more golden for daisy hearts,

For the eyelids of the eagle, another, higher

Tuck, more massive padding for the paw

Of the polar bear. No end in sight to his toil,

Always a rumpled mountain of mortal stuff

Waiting beside him, every size and shape,

And texture, each one in its turn exacting

All his creativity, patience, skill.

His working day, as long as time itself.

His pay? Nothing at all, not even thanks.

Those that he helps respond with fear and loathing.

Why does he bother, then, keep on and on?

This is his trade, this is what he was born

To do. Besides, he knows quite well the world

Would soon be barren, lacking his invention;

No one else can manage these things as well.

Perhaps that’s why he hums as he sews away,

Or whistles a bit, or even, at odd times, sings.

If You Can’t Stand the Heat

How amorously upon the kitchen stoveThe gas burner’s soft blue fingers play

On the pot’s rounded bottom! The naked clove

Of garlic, see how it clings to its naked neighbor!

See the zucchini, so saucily kissed, growing limp,

The swift swoon of the rectilinear butter,

The first stirrings and steamings of blushing shrimp,

Hear the pot-lids, excited into a stutter!

Observe, on the counter, where side by side they sit,

The beater making the molded jelly throb!

And look—for at last it is time—as the shining spit

Impales a tender tomato for the kabob!

Too fleshpot, gentle reader, really not nice?

Outside, for the asking, a world of impeccable ice

French Country-House Interior

(Lithograph by Jacques Petit)

A room in a normal house: walls, roof, no doubt

A cellar below; and yet one slowly sees

That, except for those voices down the hall, the breeze

Would be inside, the inside would be out,

With chairs and china blossoming all about

The garden, the inside green with lettuce and trees.

As it is, the colors and shapes and textures tease

Each other through the windows, smile and pout.

The people living here are probably not

Especially honest, handsome, generous, good.

It’s just as well we cannot see their faces.

For this is the kind of dwelling all have sought,

One of those undisguised and secret places

Waiting for us to come and live as we should.

Fire Dance

A life is a leaf in a forest fire,Speeding others along the way.

He who denies is blind, or a liar.

Vanity, the dreams of the choir;

Death’s commission he’ll not betray

A life is a leaf in a forest fire.

Cowards a second chance desire;

Though it steal some other’s share away.

He who denies is blind, or a liar.

Swiftly you’ll shrivel, your hopes expire,

If you wait for a gentler kind of day

A life is a leaf in a forest fire.

To heal, to love, create, inquire:

These are the only Holy-Day.

He who denies is blind, or a liar.

Each must learn to dance in his pyre,

No music else, a moment to play:

A life is a leaf in a forest fire.

He who denies is blind, or a liar.

Stone

(For Samuel Beckett)

Somewhere conveniently close beside your bed

It would be wise to keep a smooth round stone,

Perfectly black, of a size to fill the hand:

A thing as simple and good as water or bread.

Because the time will come to cry Ochone,

Oy vey, Ai-ee, alone on a bleak strand,

To tell woe’s rosary from A to Zed,

To feel both heart and mind shrink close to the bone.

And then, no better equipped to understand,

But not quite emptied out, unballasted,

You can reach out in the night and heft that stone

And hold its total blackness there in your hand,

And say: though darkness whelms me more and more,

I can go on, I have been here before.

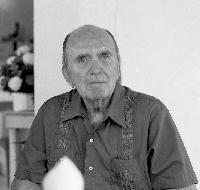

About the author

Born in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, Neill Megaw spent his childhood in New York City. As a young man, he was a ship welder, a swing band singer and dancer, and a bomber pilot in WWII with the United States Army Air Corps. He received his doctorate from the University of Chicago in 1950, and embarked on a career as an English professor teaching Shakespeare and Modern Drama, first at Williams College and later at the University of Texas at Austin.

Neill Megaw did not begin writing poetry until four years into his retirement, at the age of 69. Once he began, he was content to be possessed by it until his death at age 80. Included in this collection is the second poem he wrote: “French Country House Interior.” In just over a decade, he wrote over seven hundred poems and countless haiku, many of which were published in poetry reviews nationally and internationally. A book of his poetry, Other Voices, was published on the occasion of his 80th birthday.

Click here to read a review of Other Voices.